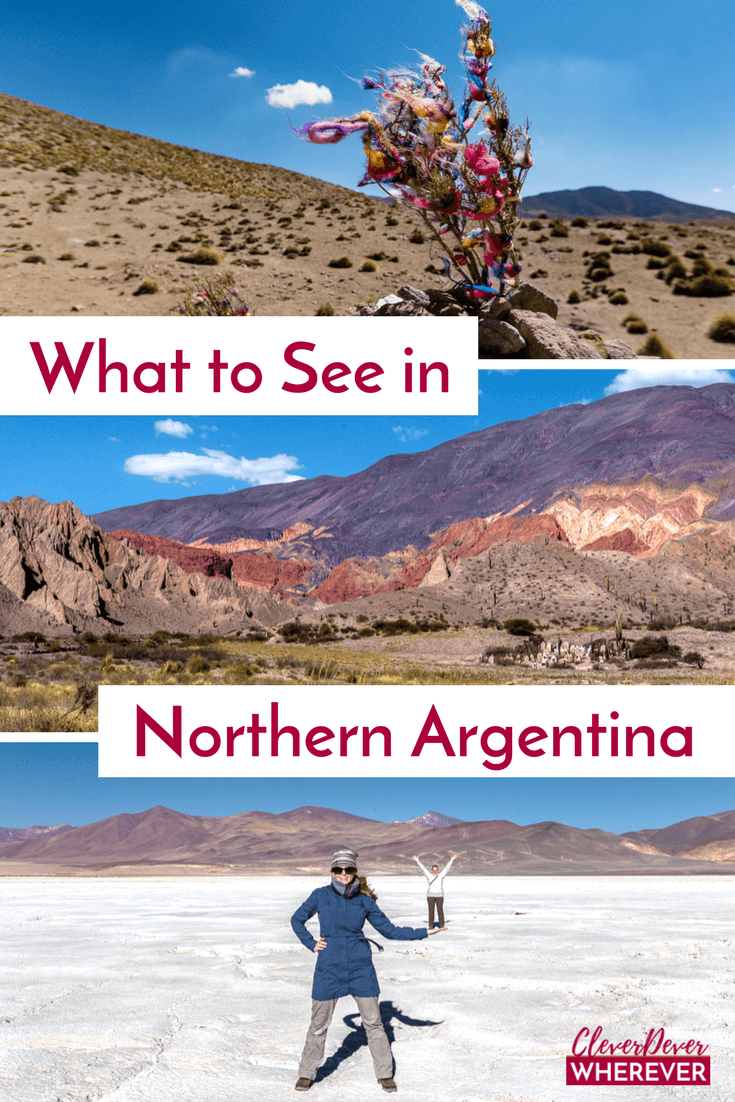

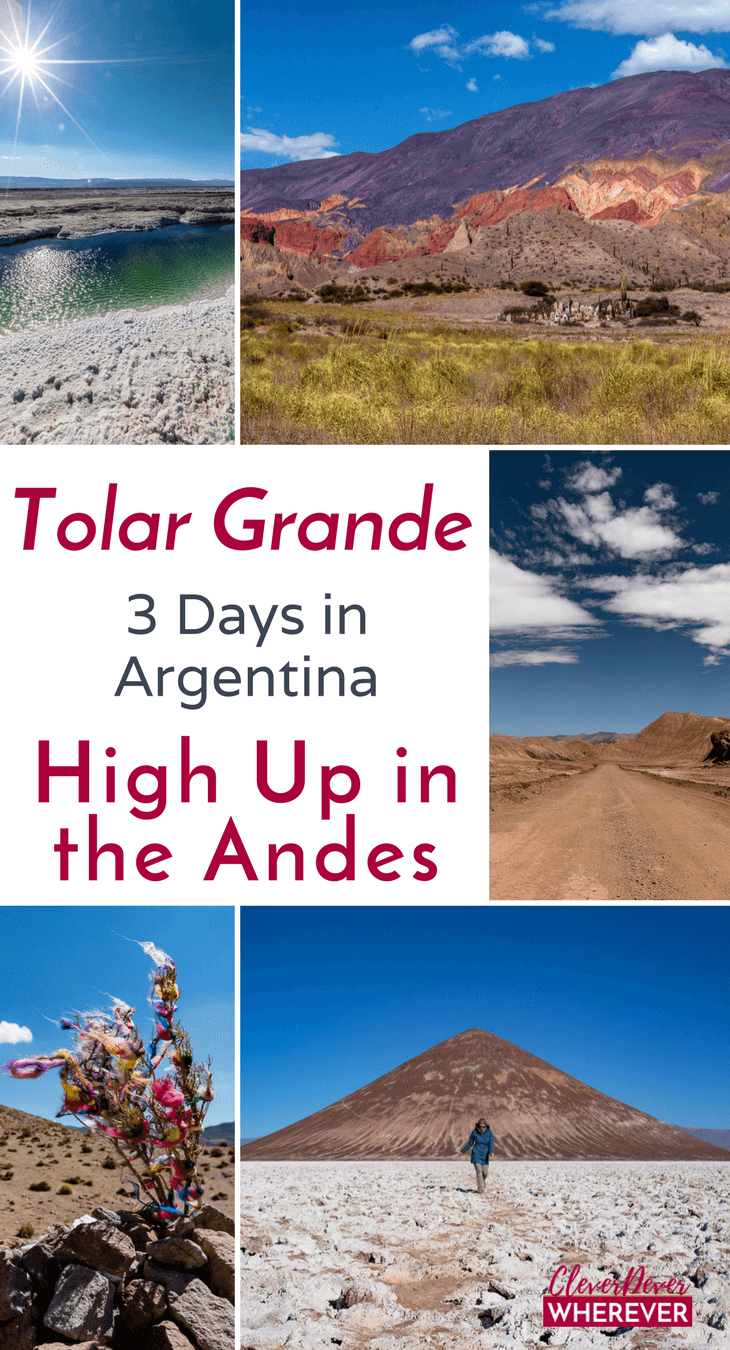

I’m almost in tears in the Houston airport. The words “Buenos Aires” glow on the sign behind my gate, and I can’t breathe. “I can’t get on the plane. I don’t want to go to South America.” I hyperventilate. “What are you afraid of?” My friend Rachel is on the other end of the phone, trying to calm me down. “Flying. Landing. The Andes Mountains. Traveling alone in general.” I’m fully irrational now, shaking as I try to understand this panic that’s washing over me, knocking me off balance and pushing the air out of my lungs. Possibly, I did the wrong kind of research to prepare for my trip. My impression of the Andes was shaped by book titles I Googled: Death in the Andes Life and Death in the Andes Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors (which means the rest of their crew experienced, you guessed it, DEATH IN THE ANDES.) When I called my mom after talking to Rachel, she said my gut was telling me something and I should turn around and go home to Los Angeles. As I watched other passengers board like nothing in the world was wrong, I considered it. Get it together, Dever. I inhale slowly and deeply and parse everything into small, actionable steps: Get in line. Scan the boarding pass. Walk the jetway. Find my seat. Order wine. Search the faces of the cabin attendants for signs of concern. The captain walks by and I grill him on his flying experience as if I’m interviewing him for the job. He rarely flies this route because he trains pilots. They’re lofty credentials, but still. “This isn’t your regular route?!?” Maybe he’s not familiar with the little trouble spots or, I don’t know, Central American updrafts or something. He gives me a sympathetic smile. There’s no way around this but through it. We take off. The catalyst for this particular journey to South America was the Adventure Travel World Summit. I joined the Adventure Travel Trade Association, a community of impressively adventurous travel professionals (that are way more adventurous than me), hoping to find my tribe. The World Summit was meeting in Salta, Argentina at the base of the Andes Mountains for a week of communing over tourism and adrenaline-fueled activities like biking, rafting, mountaineering (them), and wine drinking (me) and llama petting (also me). Salta, a charming village in the far northern reaches of Argentina is filled with colorful colonial buildings, guitar music and heel-stomping dances. That’s all I knew. Well, that and they have a range of serial-killer mountains in their backyard. Before leaving I was supposed to sign up for one of the pre-conference tours. My friend Sherry Ott and I are traveling together, and the three-day trip in Tolar Grande caught her eye. I don’t blame her: The marketing photos are breathtaking. Gleaming salt flats, mirage-like deep green lagoons, and sienna-colored rock formations dot the landscape. It’s so unearthly looking, I knew right away it’d be the closest I’ll ever get to space travel. Then I read the details: It’s a 10-hour Jeep drive to get to Tolar Grande from Salta, and the teeny village is almost 16,000 feet/4,880 meters above sea level. It’s an all-but-abandoned mining town in the heart of the Andes Mountains, the place where all the books about death are written. Why are my friends so much more daring than me? I curse her name as I sign up. The morning after we arrive in Salta, our guide Sebastian picks us up for the journey into the heart of the Andes. He strikes me as the survivalist type, which I glean from the fact that he’s wearing khakis and aviator sunglasses. The truck cab is small. I position myself next to Sebastian and immediately get a slew of anxiety-fueled questions out of the way so I don’t embarrass myself in front of new people. “Are we driving along cliffs? How bad does the high altitude affect one’s ability to breathe? How often do people get lost in the mountains? Have you heard about all this death in the Andes? Why don’t you have stop signs?” Sebastian patiently assures me that there are no cliffs in these mountains, that I’ll be completely safe, and that they don’t need stop signs because drivers know to “just jump out” into oncoming traffic. I’m not entirely comforted. After a bit, we stop to pick up the third of our four adventurers, Keri from Vancouver. She’s full of energy and doles out friendly introductions and snappy comebacks even though it’s not yet 8 a.m. She must be some kind of wizard. Next we pick up Paul, a charming Mexican man with a quick smile and a mop of unruly hair that we’ll lovingly refer to as a yak-fro in the coming days. With one massive squish, Sebastian squeezes us all into his Toyota and we’re on our way towards the infamous mountains. After several hours of driving under overcast skies and the haze of gravel dust, we emerge through the clouds into a Technicolor-filled world. A brilliant blue sky borders purple and orange mountains. At their base, adorable tiny houses cluster together for warmth. Sebastian points. “That’s an Andean cemetery,” he says. Seriously? We keep driving. And driving. Finally, eight hours, two coca teas, and four naps – possibly from oxygen loss – later, we pull into Tolar Grande, the village that will be home base for the next two nights. Tolar Grande translates to “Big Bush,” which prompted ridiculous jokes from all four of us and an irresistible Sir Mix-a-lot parody by Keri and I. Tolar Grande is a mining town past its prime by 80 years — after a military coup shut down the nearby railway system, its lifeline was cut off. Lithium mining in the salt flats and the hope of tourists are its two chances for a comeback. A tumbleweed the size of a Swiss exercise ball blows by, and it’s hard to understand how this town hangs on. We find the only restaurant in 125 miles/200 kilometers and sit shivering in several layers of wool and technologically advanced materials. There is no menu at Llullaillaco restaurant. You get whatever is being served and you are hashtag grateful because you got it. Seriously: While we’re waiting, a group of motorcyclists from Buenos Aires arrive, dusty and cold from a long ride, only to be turned away because they didn’t call ahead. In a town with an abandoned train station, food deliveries have to be planned in advance. We order one 40-ounce Argentinian beer to share between four of us, but we are far too dehydrated and exhausted to finish it. Even so, my head swims as if I had had a couple beers myself. We are 12,500 feet/3,800 meters up, and the altitude is getting to me, getting to us all. I try to focus on Paul’s crazy hair and Keri’s story about Surinamese snakes biting tourists, but it’s like we’re all underwater, talking to each other in slow motion. After dinner, we retreat to our rooms in the back of the restaurant. Sherry and I plug a space heater into the one electrical outlet that doesn’t show visible melted burn marks, but we still have to wear half of our clothes to bed. This, my friends, is definitely an adventure. The next morning, it’s finally time to really venture out into the Andes Mountains. The first lesson: It is windy. Sebastian was right about the lack of cliffs. Though it makes for a less stressful drive, the flat land surrounding the mountains means there are no windbreaks. The occasional land formation is forced to stand alone like a singled-out soldier. There are mountains in the distance, but they are little more than a backdrop, jaggedly keeping the wild blue yonder from appearing bored. … Which doesn’t help when you need to pee. Walls of wind come at you in angry bursts like a bouncer breaking up a fight, and often, the only shield is the pickup truck itself. Even then, I use my index finger as a wind vane, squatting in the direction of the prevailing winds. Together, the four of us explore. We wow at neon flamingos in unison, scream like banshees when the wind throws our hats across the desert, jump probably 50 times for photos on the salt flats, and laugh until we cry at each other’s far-flung travel tales and the indigenous word puna. As we drive along the flats, the close quarters of the truck start to feel more like a tool for keeping each other warm than an invasion of space. Falling asleep on one another’s shoulders seems totally normal after 24 hours together. At one point we were on grassland so elevated that it felt like we were level with the mountaintops themselves. Oxidized green copper and rusted iron red peaks bordered a wide-open space. It was so beautiful that we stopped and Sebastian turned off the truck’s engine. Slowly at first then all at once, beautiful, fine-boned alpaca-like creatures began to bounce across the landscape as if it were a giant shrub-covered trampoline. These vicuñas, Sebastian explained, could only be found in really high elevations. As we sat and watched them, it struck me: I was on top of the world. Literally. I was here, I was doing it, and somehow, it was not scary. It was incredible. Our final morning, Keri gets food poisoning. (As if sharing a shower and peeing outside together hadn’t brought us close enough.) We help her the best we can by sharing first aid kits, toilet paper and whatever small comforts we had between the four of us. We have each other’s backs in ways you don’t imagine you would after knowing someone for only two days. Driving back to Salta, we stop to take photos and hike around the Devil’s Desert, a burnt orange sprawl of rock formations 11,000 feet/3,350 meters above sea level. I stand on a rock face as Sherry readies her camera, then all at once I inhale thin air and launch myself upward. “YEAH!” I roar. I feel like a superhero, flying high above the earth. A week ago, I was so afraid of this trip I could barely catch enough breath to walk onto a plane. Now look at me: I’m jumping over mountains on top of the world. I really do feel like a badass. My feet return to the earth as I fill my lungs with mountain air. I look across the rugged landscape towards my new friends and it surprises me how much they feel like family. Sherry, camera in hand, captures the moment. Keri leans on a rock, the grasp of food poisoning fading. Paul, his hair reaching peak yak, hovers by her, making sure she’s okay. You know when someone says you can’t do something? Somehow, because it’s someone else, it’s easier to dig in and do it just to prove them wrong. When it’s the voice inside you telling you can’t, it’s harder. But that voice is fear. How much greater is it to dig in and prove to fear that it’s wrong? Before we squish back into the truck to return home, the four of us do one last jump. We holler across the red expanse of the Andes and feel like the only humans on Earth. It’s magnificent. We’re exhilarated. We’re fearless. “It’s an all-but-abandoned mining town in the heart of the Andes Mountains, the place where all the books about death are written.”

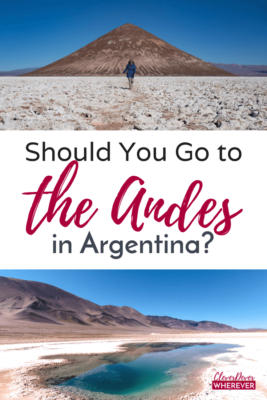

“It’s so unearthly looking; I knew right away it’d be the closest I’ll ever get to space travel.”

“There are mountains in the distance, but they are little more than a backdrop, jaggedly keeping the wild blue yonder from appearing bored.”

Has there been any place that you were afraid to go, but you did it anyway?

What happened? Tell me!

Read More

About Argentina

About the Author

Juliana Dever

Hi. I’m Juliana Dever and according to science I have some sort of "exploration" gene. Embracing this compulsion, I spend a lot of time hurtling around the planet in metal tubes experiencing other cultures and writing humorous essays about it. Enjoy.

5 Comments