Beating drums reverberated through the small wine village of Mád. The rhythmic boom was the call for everyone to come out into the streets for an announcement. This is how the Hungarian gendarme communicated with townspeople in the first half of the 20th century.

It was May 1944.

“They went on the street and put on the arms of each of them a yellow star.” Barnabás Fehrér, a second grader at the time, recalls the day his friends were rounded up.

He remembers Jewish residents were to gather enough food for three days. The Jewish population, around 350 out of a town of 3,500, was then taken to their synagogue on the hillside and locked in. After three days, the families were transferred to a ghetto and then sent to Auschwitz to die.

“They took them somewhere. Since I was seven years old that time, I had no idea where did they take them.”

I’ve stopped here during my visit to the Tokaji wine region, an area known for making sweet wine of the same name since at least the 12th century.

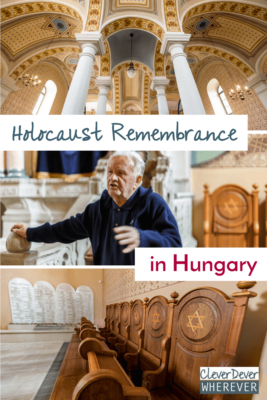

But this stop wasn’t about the wine. It was to see this gorgeously restored Baroque synagogue in the Hungarian countryside. It was also to hear the story of the man who cared for it most of his adult life.

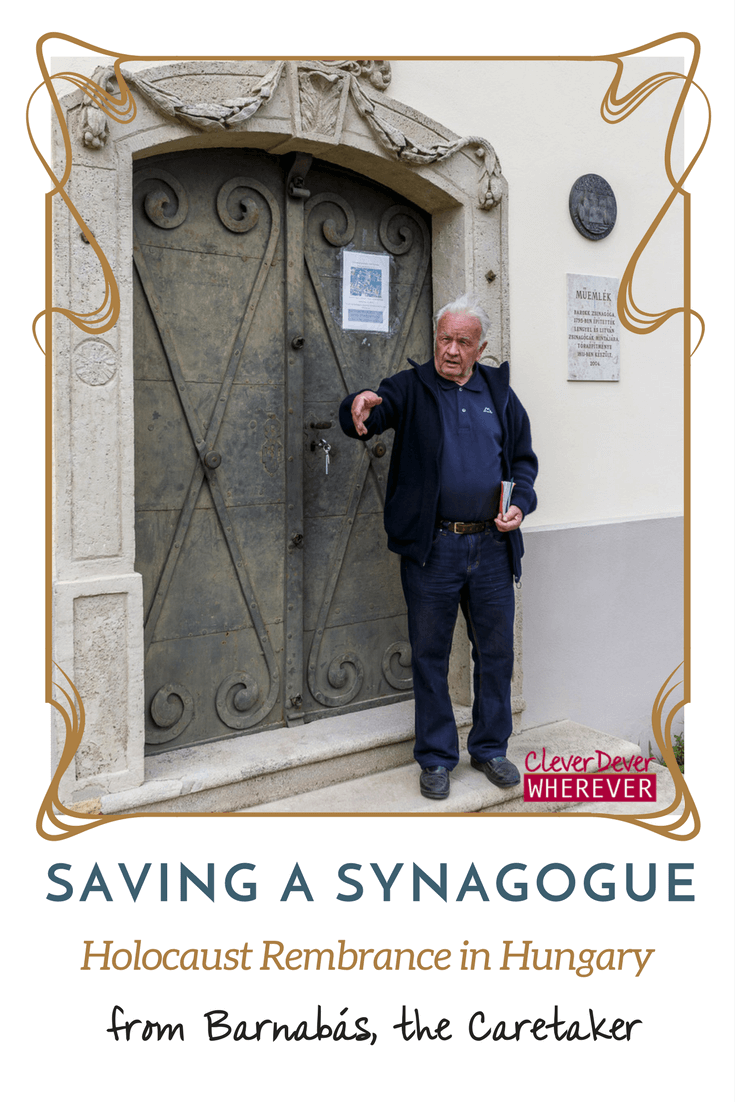

What’s exceptional about Barnabás’s effort is that it was voluntary. Though he lived nearby, he could’ve left the building to decline over the decades. After all, he was a Roman Catholic with a full-time job overseeing Mád’s wine production. He had no obligation to care for the crumbling, unused structure. He could’ve stood by and watched it fall into complete decline. But he chose to care for it, in honor of the friends he once played ball with who were taken all at once on a spring day.

He shares his memories during and after World War II in snapshots. Though they’ve faded over time, each one brings a moment into focus. Sometimes the memory lingers over grim details, sometimes, lucid recollections.

“Before the war Mád and Tokaj-Hegyalja (the name of the whole area) was famous for the vineyards and the wineries. All main occupations were in connection to viniculture. There was a huge winery in a nearby village and my father worked there for the owner as a vinedresser. I grew up with those kids in the winery.”

He carried the largest key I’ve ever seen. Gothic in design, it opened what, from the outside, is a modest building. There is nothing to tip off a visitor of what’s inside.

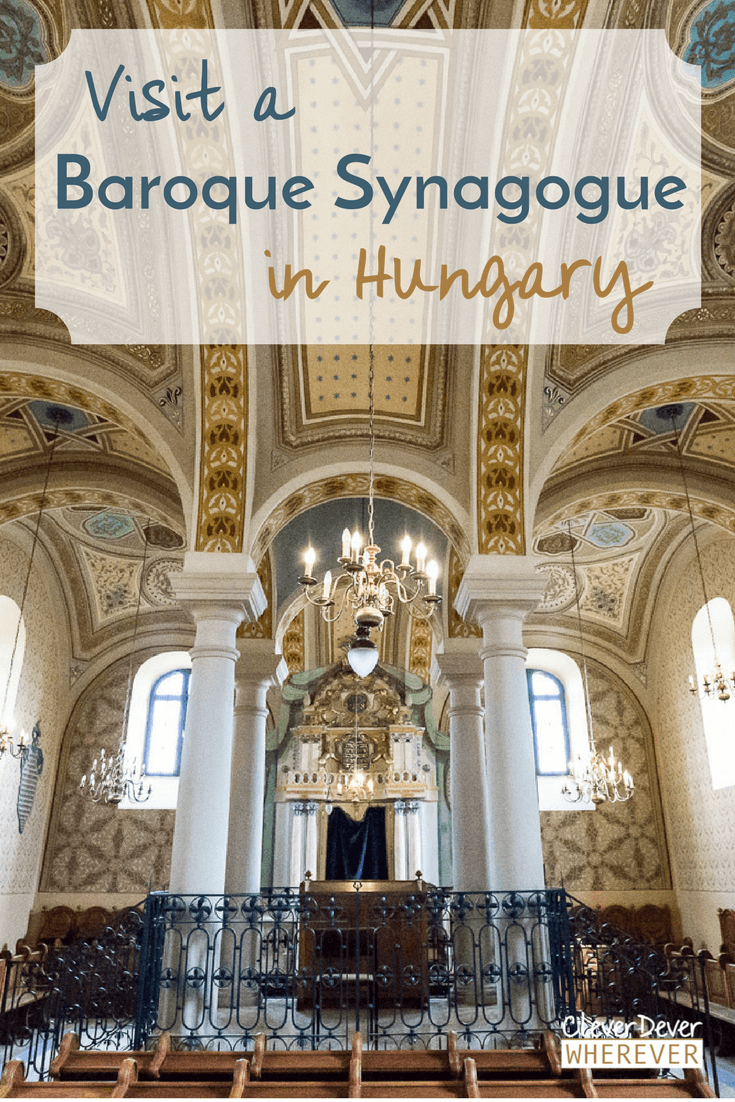

Built in 1795, the ornate interior glows with reds, golds and blues. Sun fills the main room with light, illuminating the intricate patterns painted on the ceilings and walls in lustrous detail. It brings an odd backdrop of triumph to a story charged with emotion and the lowest depths that humans can sink.

“It was a in a very bad condition: nobody took care of it until that point. I felt sorry to see it getting wasted, so I started to take care of it myself.” He looks around the sanctuary, the shambles that it was a flashback now.

“When I started my work as a caretaker, the synagogue was in a very deteriorated condition. I started to clean it myself; I started to bring it to a better shape. I called my friends and we started to take out all the rubbish and trash.

I wander throughout the main floor. Barnabás speaks in Hungarian to a couple of women, two senior citizens who are in from Budapest to see the synagogue. They respond with wonder, disappointment and sadness at his tales. I wish I could understand him in Hungarian instead of translated English.

It’s hard to capture how grand this small place of worship is with a camera. Even my wide angle tells only half a story. Barnabás allowed me to go upstairs and take pictures from above. It’s like a mirage where the exterior is a little tent and the interior is a huge palace of opulence.

“Since that time I have been taking care of it, being myself a Roman Catholic. I clean it, guard it, making tour guides, welcoming guests. For fifty years now. I am already retired, so I have more time for it now, but even when I was working, I always took the time for it: often I had to come home during midday, when guest were coming.” He continued.

“But now (that he is retired) it is much easier since I live just under the synagogue, so when any visitor comes, they are able to find my phone number on the door of the synagogue and I will be there within 5 minutes, and I tell everybody everything that can be known about the synagogue of Mád and the Jewish people of the town.”

This man is not just a caretaker, but a witness to the atrocities of the past. His dedication was not only to the synagogue, but to bear witness to his stolen friends and their families. He was there to “tell everybody everything…of the Jewish people of the town.”

We stood in front of four large marble tablets engraved with the names of the 343 villagers who were murdered at Auschwitz. Winemakers, tavern owners, butchers, and childhood friends…these were the people memorialized on this wall.

I ask if anyone survived, if anyone returned.

“There were about twenty. The elder people died after a while, but the younger ones moved to bigger cities, because after the war in the Rákosi system it was not possible to own businesses. Mainly these families were merchants originally. So they moved to cities, or went to Israel. There are still people who come from Israel from time-to-time to visit the synagogue.”

Barnabás finishes our tour in the entryway of the synagogue. Next to him is a small box for donations that pay for the continued care of the building and grounds.

For over fifty years Barnabás, a Christian, has poured his time and care into this house that he’s never worshiped in. He’s honored the lives lost and told the stories no one else is left to tell in a rural town touched by the horror of hate.

Barnabás is a symbol of the peaceful coexistence that Jews and Christians once enjoyed in this area. I’m honored to have met him and heard his story, a story of holocaust remembrance that transcends time and faith, keeping alive the legacy of a people he once knew.

Mariann Frank, project leader of the Footsteps of Wonder Rabbis project – which seeks to restore and complete the histories of Jews in the region – also contributed to this story.

She gave a little more background on the building’s restoration.

“The Synagogue was in a very bad condition, no one used it for anything. After the war, when the Jewish Community of Mád is ceased, the Hungarian Government maintained it and it become a national heritage, but did not invest money for the maintenance. In the 1970’s one of the descendants of Rav Reinetz (he was one of the well-known rabbis of Mád), donated to fix at least the roof of the synagogue, because lightning burned it down in the ’60s.

“Later, András Román a famous Hungarian architect who was involved with monuments architecture contacted the World Monuments Foundation and they gave some donation to start the synagogue’s preservation. Then the Hungarian government played the bigger role to renovate the synagogue.

“The renovation started in 2000, the leading architect for the renovation was Péter Wirth. In 2004 they finished the renovation and in 2005 received the European Nostra Prize.”

How To Visit the Synagogue in Mád:

Check here for train information to the village of Mád.

You can also arrange a visit through Mariann’s website.

Or, you can ask your guide to stop there (like I did) while taking the wine tour through the Tokaji region. I used Taste Hungary, and I definitely recommend them for a tour of Eger and Tokaji. They’ll pick you up and return you to Budapest, or arrange for an overnight stay in the area.

Special thanks to Ábrahám Gyöngyösi for his immense translation work and to one of my favorite people Julie Callahan of World in Between for suggesting I visit Mád and speak to Barnabás.

2 Comments