I rarely turn on the TV in a hotel room. But after a long day at a world airline conference in the upside-down of Australia, I needed connection to the outside world.

Click.

Thick black smoke billowed from a skyscraper. I had no idea what movie it was, but I sat down on the bed, kicked off my shoes and watched. There was a heightened strain to newscasters’ voices. The crawl across the bottom of the screen snapped me to attention. This wasn’t a movie.

Even though it was nearly 11pm, I called my boss’s room.

“Turn on the TV!”

We watched together, confused. An aircraft curved through the blue sky, barreling straight into the second tower.

“Oh my God.” She had spent the first few decades of her career as a flight attendant. No doubt she vividly imagined everyone on board in those seconds.

Silence.

What were we watching? Was this real life?

The next morning, gathered in Brisbane with most of the world’s airlines, we congregated. From Finland, from Thailand, from Saudi Arabia, from the U.S., like zombies we drifted the convention floor. American and United Airlines representatives were trying to call home and mostly failing to make a connection. They knew people on those planes.

So did Saudi Arabian artist Abdulnasser Gharem. Two of his former high school classmates were on those planes. Only they were the hijackers. On September 11, 2001 he and his family watched the towers collapse. Everyone gathered around the television in his childhood home in Khamis Mushait. They were shocked.

Pause.

Considered one of the most influential artists in the Persian Gulf, self-taught Abdulnasser Gharem’s work reflects his unique perspective. As a Muslim, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Saudi Arabian army, an Arab and an artist, Gharem seeks to understand the path each person chooses in life. Why did his classmates choose to be on those planes and turn them into weapons of destruction?

Islamic Art in the Time of the “Unthinkable”

Gharem’s collected works explore some of those questions and are now on exhibition through July 16th at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), on Wilshire and Fairfax. I saw “Pause” last week. The thought of a Saudi Arabian artist creating Islamic art from 9/11 surprised me. What would he have to say? What would he be allowed to say?

“What we learned on September 11 is that the unthinkable is now thinkable in the world.”

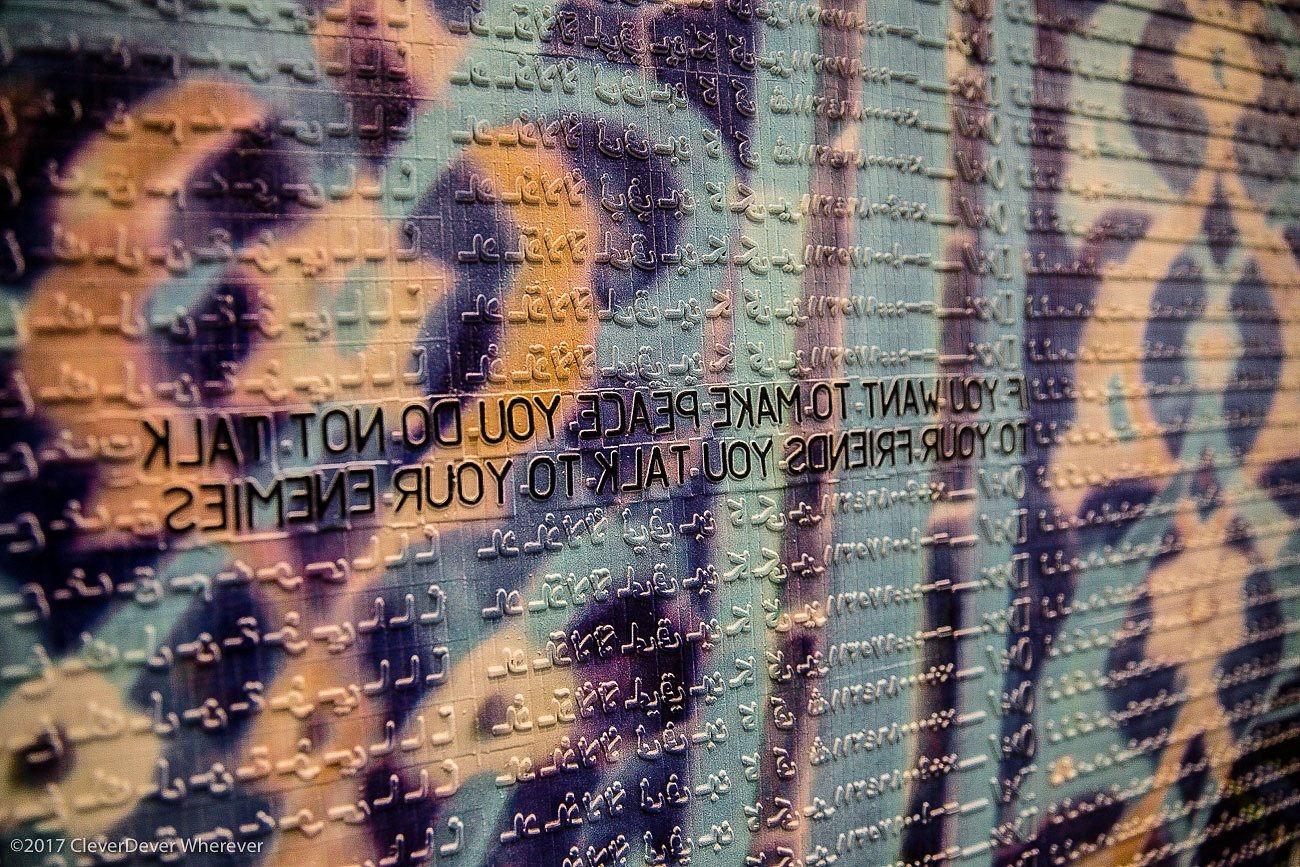

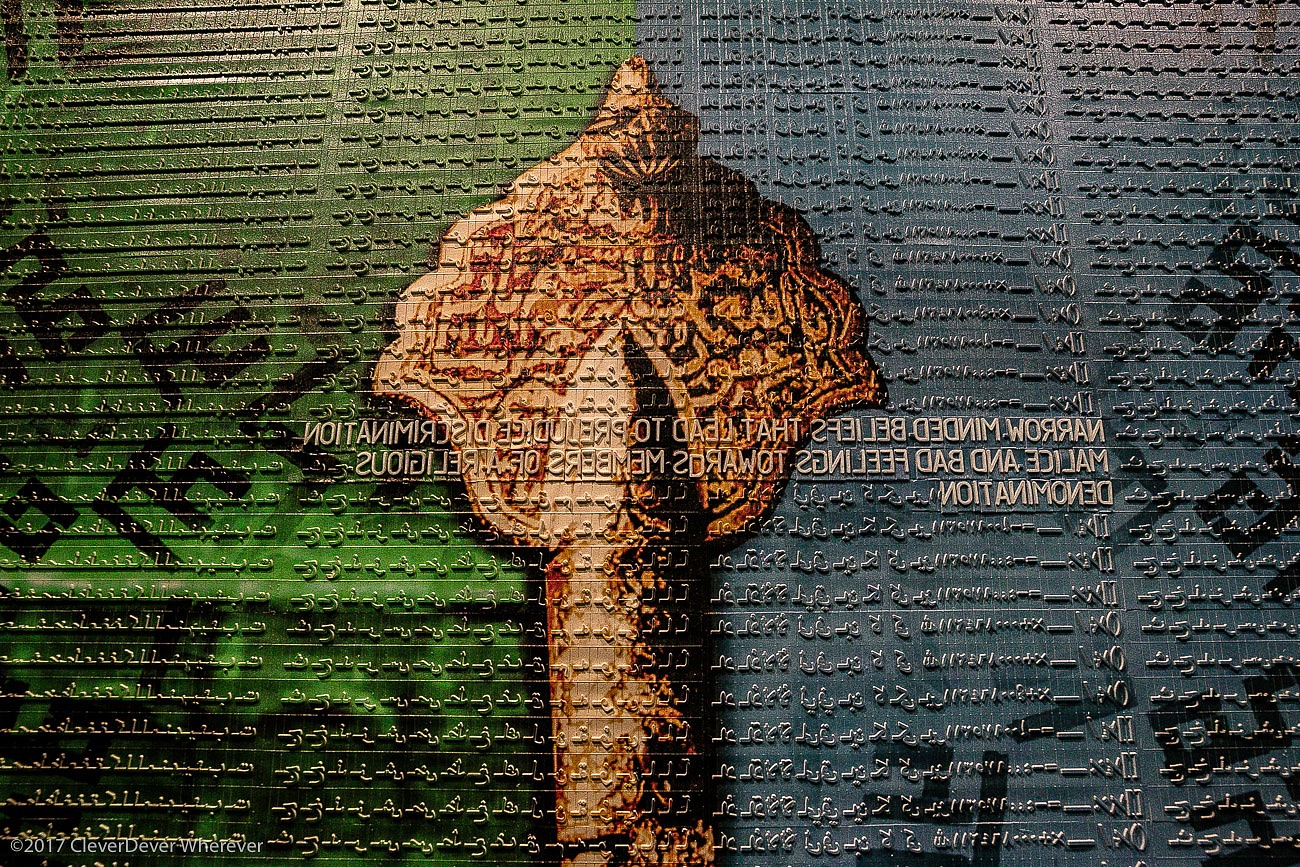

Raised up from his composites like braille, this quote and many others are spelled backward compelling you to pause and figure it out. It’s an unusual medium, canvasses formed with pieced-together rubber stamps. It was so hard not to run my fingers across the letters.

“Pause” is both the name of the exhibit and his diptych of the twin towers. The moment I took in the two smoking towers rendered in tiny-cut rubber letters, I felt it immediately in my stomach. Appearing gray, they form a literal pause symbol. Upon closer consideration the towers are not gray. They are the blending of black and white stamps, English and Arabic letters.

There is so much to absorb in Gharem’s work. With just over ten pieces on display, it would be easy to wander through the exhibit in a matter minutes. But to do so would be to miss the deeper meanings woven into every piece. The longer you pause, the more those meanings reveal themselves.

In the main room, the sheer size and dimension of the next few pieces were so large, I felt like Alice in an Arabian Wonderland.

A massive, decorative, 3D government stamp rests next to its imprint that reads “In accordance with Sharia Law.”

Immediately I blanch. I’m not fond of bureaucracy or the idea of church and state mingling. Long ago I extricated myself from an extreme Christian fundamental group. I’m not okay with absolutism from any religion.

It’s so large that I couldn’t ignore it. What does this stamp mean? It’s the same size as me, perhaps to compare the value of humans vs. dogma. Exaggerated in size, is the idea of imposing theological permission more important than the nuances of humanity? It almost seems cartoonish.

To the left of this is a gigantic dome, with two distinctly different halves merged to form a cupola. On one side is an ornate soldier’s helmet covered in script, the other a mosque; symbols of war and peace confronting one another. You can’t help but consider how much ideologies, no matter how peaceful the tenets, give way to hatred and war.

Nearby, the rubber stamped painting “Ricochet” is an eye-catching kaleidoscope of Islamic motifs. Gharem layers mesmerizing geometric shapes and rich contrasting colors over a fighter jet. It suggests actions set into motion that reverberates continuously.

“We thought we could liberate a country just by walking in the door” is spelled out backward in rubber stamp. Again, I want to run my fingers over it, but refrain.

I’m pulled into a conversation I had with my Jordanian friends while visiting Amman earlier this year. We talked about our countries’ complicated relationships. We discussed what role the United States has played in a region that sees stability rise and fall as precariously as two sides of a seesaw.

I spent several weeks in Jordan in 2013 and loved it so much I went back this year during my travels in Oman and United Arab Emirates. It’s been one of my biggest surprises in all of my globetrotting.

Almost without exception, everyone I’ve met across the Levant and the Gulf States LOVES America. More so than some places I’ve been to in Europe. I’ve been greeted with so much enthusiasm it takes me aback.

All across the Middle East I heard “Welcome to my country!” again and again. Genuine friendliness and a fondness for the United States were repeated wherever I went.

Welcome.

You can’t visit the region without multiple offers to join families for dinner at their homes. I’ve been hosted by a fisherman in Oman, camped with Bedouins in the remote desert, and served a spread of food so vast in Amman I felt they had mistaken me for royalty.

Each time, I try to understand this divide that has increased to a frenzied point in our histories today. Which is why Gharem’s work is so important.

Why should we care what a Muslim, an Arab thinks about 9/11? Isn’t this our tragedy to process? Aren’t we the victims of a horrific attack perpetrated by his countrymen?

Absorbing Adbulnasser’s artwork means realizing that terrorism is a global concern. It destroys lives everywhere. He and his family – and so much of the Islamic world – were just as sickened watching 9/11 unfold.

If we can begin to understand each other, we can begin to understand our shared humanity. We can try and choose a different path towards peace.

Seeing Abdulnasser Gharem: Pause at LACMA is an excellent step towards that.

Tips for visiting Abdulnassar Gharem: Pause at LACMA

Now on view through July 16, 2017

LACMA

5905 Wilshire Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90036

Museum hours:

Monday, Tuesday, Thursday from 11 am–5 pm,

Friday from 11 am–8 pm,

Saturday and Sunday 10 am–7pm.

LACMA is closed on Wednesdays.

Tickets can be purchased online or at the ticket office out front.

L.A. County residents receive free general admission after 3 pm every weekday LACMA is open.

This post was sponsored by LACMA, but all opinions are my own.

2 Comments