Updated January 14th, 2020

“Zaza knows that the wine made in qvevri takes out all concern from the body, it helps the heart to work properly, and all different kinds of diseases. Zaza says to ‘drink wine made in qvevri daily.’”

Zaza is not the only one who says this. It’s more or less the slogan of the entire country of Georgia. Maka, who is translating for Zaza Kbilashvili, one of the few qvevri makers in Georgia, smiles in agreement as she repeats the phrase.

“Drink Wine Made in Qvevri Daily.”

I think it’s what they stamp in your passport when you arrive.

But what’s a qvevri?

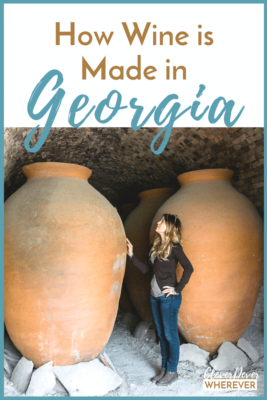

Pronounced KWEV-ry, the gorgeous egg-shaped vessel is a massive clay pot that’s buried in the ground up to its collar. Made with little more than earth and human handiwork, these giant clay urns are one of the purest creations. It’s a true collaboration between Mother Nature and man.

Smaller qvevris for making wine and urns for pouring wine at the National Wine Agency. These pieces were found throughout Georgia and date back thousands of years.

It’s purpose: to make some of the most fascinating wine on earth. For at least 8,000 years Georgians have filled these qvevris with grapes and let the earth work its magic. The clay cauldron allows the juice and skins to ferment together, turning the fruit into a wine like you’ve never tasted before. It’s wild and rustic, earthy and richly tannic.

I’m in Kakheti, in the village of Vardisubani. Maka calls it the district of the roses. In this eastern region of Georgia only one other family makes qvevris that supply the entire country their winemaking crucible. Zaza’s family has been crafting these pots by hand for four generations now. He, along with Maka, explains how he makes each qvevri by hand.

“He brings clay from the forest, three different kinds of clay. He uses clay specifically good for qvevri. It takes experience to know which is the good clay. Clay that he uses contains lime, which has an antiseptic.” She crumbles the purplish earth between her fingers.

Maka says the clay is so good that if she smears it directly on her face it will clean it. I feel like there’s another step in that equation, but I get her point. Let’s get back to this daily drinking thing though, because I hate missing out on health crazes.

As if reading my mind, Maka makes her physician-approved case.

“A few days ago Zaza had guests and some of them from the group were doctors. They approved that the wine made in qvevri is good for health. But if you drink too much, more than enough, it never helps. It will be harmful.”

Who’s to say what the correct dosage is though, really?

We move into a small stone building filled with oversized clay bellies resting on stilts. They are so large it’s like an Alice in Wonderland effect. I feel so small.

How Qvevris Are Made

Zaza makes a rolling motion with his hands and explains the building process in Georgian. It’s a language that is vivid, round and punctuated with staccato for emphasis. Maka translates.

“He makes these kinds of layers, but bigger ones for the building construction. And then with his small fingers, he begins to make coils. From the bottom, then every two days he adds, adds. If he wants to make the bigger one he makes big belly, if he wants to make the small one, then narrow and slim like me. “

She has a huge smile that glows in the dimly lit room. The clay is still moist and the room has a coolness that makes it feel like a basement even though it’s above ground.

It takes Zaza and his father about two to three months to finish eight qvevris at a time. They are about 1500-2000 liters and stand around seven feet tall. No two are exactly alike.

We head outside to the kiln, which I do not realize is a kiln because really it looks like a brick cave stuffed with flower pots on steroids. There’s room for eight qvevris propped upright.

After the handmade pottery is moved into the kiln, the firing process lasts for a week. During this one week, the temperature slowly moves up in 100-degree increments. I really had no clue this was such a delicate process.

“Only in the central part, there is a small free space left to be able to put the wood and to set the fire. You see inside? These are the only places for where the fire goes out and where the oxygen comes inside.” Zaza gestures.

I walk inside at Zaza’s invite. The firing process for these babies is complete, and the air around them is cool. I half expect to see a Mad Hatter or a bottle that reads, “Drink me” nearby. Considering we’re in the land of wine as a daily prescription, this is actually likely.

“During this one week, Zaza and his father can’t sleep because they are very careful to increase the fire and not to let it fall down.” Zaza and Maka continue, overlapping Georgian and English as the story unfolds.

“If something happens and they fail then all their job will be in vain. So when it’s the firing process, you see the qvevris are a gold color and the fire is simmering inside. You can’t approach this area.”

Wandering around these towering objects, it’s inspiring to see the level of artisan skill that still exists. But even more so, to see the love and dedication that goes into making wine here in Georgia. Each step towards its creation is so sacred, an entire country’s lifeblood.

We move to the last part of the process, where the exterior of the qvevris are covered in limestone cement. We’re looking at two that are lying on their sides. Zaza leans on them to finish his story.

Making Qvevris – A Family Tradition

He’s a sturdy guy who smiles easily. Once a pro wrestler, he’s still beefy. He uses that brawn to pick me up and stuff me into one of his finished qvevri displays. I don’t object because really, how often does one get stuffed into a winemaking container? Also, it’s a pretty cool place to record Instagram stories what with the good acoustics and all.

He didn’t always expect to be following in his father and grandfather’s footsteps. With a degree from the University of Tbilisi, Zaza was on the faculty. But, he explains, amidst his “good job and good income in the capitol city, my family was calling me.”

He left everything and moved back to his village to carry on the tradition; to learn to hand make the precious clay vessels that keep Georgia’s winemaking heritage alive.

The way he talks about his creations is as if there is some magic in them that comes from beyond.

“Qvevris are like humans, they must breathe. It knows what temperature is good for wine and creates this temperature. Qvevri has the advantages that if a grape is sprayed with chemicals, the clay knows to pull the chemicals away.”

Zaza says during fermentation, grapes begin to move within the vortex. At the perfect time it stops moving, and each layer settles down to the pointy bottom. The process by which Georgian grapes become wine seems handled by the ingenuity of the qveri’s shape itself.

Drinking wine is seriously a daily thing here in Georgia. No wonder everyone is so happy all the time.

After Zaza pulls me back out of the qvevri I ask him what he loves about his country.

“First of all, qvevri made Georgia more famous. The qvevri is so unique, it makes the perfect condition for wine to be made.” He grins like a Cheshire Cat.

I suppose I couldn’t have expected another answer.

Drinking Wine Made in Qvevri Cures What Ails You

He takes me into a small brick room, which appears to be built, I’m thinking, just for drinking. It’s set up with shot glasses, cheese and bread. Zaza holds up his treasured chacha for us to gaze upon.

Similar to grappa, it’s a spirit distilled from the remains of the winemaking process, the grape skins. Somehow Georgians do shots of this all day and seem totally fine. These people are hearty.

He pours us each a shot and toasts to us.

Again Zaza speaks of the medicinal properties of the alcohol like we are at some kind of clinic lining up with ailments. “It helps with digestion. Also, you can rub it on your chest if you have a cold.” I’m pretty sure I’m fine, but I’ll remember this for next time.

We raise a glass of Georgian qvevri wine and toast to our health nonetheless.

“Gaumarjos!” we all clink and take a large gulp. The warmth rushes through me. I’m feeling better already.

The amazing folks at the Georgian National Wine Agency, all of whom drink Georgian qvevri wine daily, made my trip possible. All opinions my own, and I am also of the opinion that I should drink this magical wine daily.

Have you had Georgian qvevri wine? What did you think?

Read More

About Georgia