“Stick your tongue on it. Go on.” Besides bored kids in winter, does anyone ever follow this suggestion? Yet here I was in remote Mongolia, holding sun-bleached fragments of bones in my palm, and figuring I should probably put them in my mouth. You know, for the sake of SCIENCE. My unusually patient guide, Bulgaa smiles at me, and urges me again to lick the chalky pebbles.

It wasn’t an easy place to get to, this bastion of dinosaur graves in central Asia. But it was definitely a place the Mongolians are extremely proud of. The Flaming Cliffs of the south Gobi were an area of great discovery back in the 1920s when American naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews drove across the parched desert leading an expedition, all the way from what was then Peking. It was there that Roy found the full skeletons of two predatory dinosaurs (that had apparently fought each other to death) and made the first discovery of embryonic dinosaurs, petrified inside their un-hatched eggs.

Seeing how I LOVE flying, taking this turbo-prob plane across Mongolia was a nerve-wracking, yet visually-stunning experience.

For our group, a small, curious assortment of Americans, Bulgarians and Canadians this is the first stop outside of the main city, Ulaanbaatar. Getting to Mongolia itself was an 11-hour flight from San Francisco to Seoul, and then another 3-hour flight from Seoul to UB (what locals call Ulaanbaatar). Next is a one-hour prop plane ride down to Dalanzadgad, the main, and pretty much only, town in the Gobi Desert.

From there it’s a 90-minute ride in four-wheel-drive jeeps across an empty desert. No roads, no visible landmarks – just rocks, your Mongolian driver Muunii and his favorite songs about horses on heavy rotation in his tape deck. I know what the songs are about even though I don’t speak the language because every once in awhile a ‘neighhhhhh!’ pierces through the vehicle like a terrifying moment of the Godfather as I try to drift off to sleep.

Our first ger camp (a traditional nomadic round tent, known more popularly by the Turkic word yurt) welcomes us with a life-sized Tyrannosaurus Bataar at its entrance. An Asian contemporary of the T-Rex, this replica is a vicious fiberglass dinosaur that looks out over the desert with irritation, tiny arms and a motionless warning glare.

We stop at our tents to unload (we’re only allowed one small duffle bag filled with bare necessities on this leg of the journey), have a quick red cabbage and canned pineapple lunch, and get back in the jeeps. Finding dinosaur bones in this far-flung region of our globe is certainly a journey remote. We drive another hour towards the desert surrounding the Flaming Cliffs, an 80-million year-old dried out ocean floor turned fertile fossil field in the hopes of getting lucky, paleontologist-style.

The discovery of new dinosaur bones near the Flaming Cliffs. Though maybe it was staged for us tourists. We don’t know because nobody ever got down there to lick them.

“You are very lucky” Bulgaa tells us as terra cotta-colored rock faces grow larger on the horizon. “Recently, they have found more dinosaur bones and the driver knows where they are.” We park. Muunii leads us to a small pile of what, if you squint and imagine a carefully arranged museum display, does sort of maybe kind of look like some version of vertebra. This is where the lick-mus test of questionable scientific origin gets introduced.

According to Bulgaa, one can tell if any of these scattered alabaster fragments are indeed dinosaur bones based on whether or not they stick to your tongue. Seriously. My compatriots begin picking items out of the dirt and sticking them in their mouths like curious chimpanzees.

I hesitate. I wonder, how many people have already licked these things? And even if it IS a dinosaur bone, what am I supposed to do with this skeletal scrap? It’s illegal to take it home, and even if I smuggled it, do I put it on a shelf at home and then when friends come over say “Hey, that white chip over there – it’s a dinosaur bone. Don’t believe me? Lick it.”

Looking out over the Gobi, there are segmented skulls, fractured femurs, teeth and other sundry remains lodged into or sitting on top of the cracked earth. Most likely have met their demise in the recent past. Even if I do lick it, do I really have a developed enough palate to discern dinosaur matter over, say, a camel?

There are millions of bone fragments here in the desert. Who has time to lick them all?

I watch the others sticking bone after bone to their tongues, lighting up when one sticks. What the heck…when in Mongolia, I guess. I begin with the first chip. No sticking. I throw it down, ibex possibly, I think to myself. Next one up to my mouth and…pthittt…sand, but no sticking. Whatever, probably snow leopard. I put a third bone fragment to my tongue. It sticks! It actually sticks! I maybe have a velociraptor on my hands! Or rather, on my tongue! Bulgaa smiles, Muunii laughs. They point at me delighting in my discovery and speak quickly. Are they reveling in their own joke, the way Venetians must get a kick out of convincing tourists to cover themselves in pigeons?

But frankly Mongolians don’t strike me as practical jokers. I think they are proud of me. At least that’s what I choose to believe. That, and the fact that I walked across the Gobi Desert today and connected with a sliver of Cretaceous history.

I think I found a dinosaur bone, you guys! Or at least I licked some white rock!

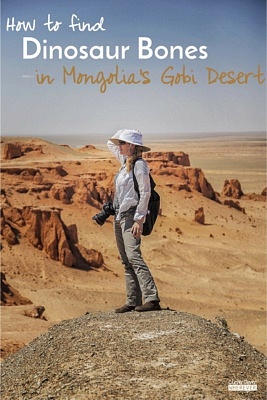

Looking out over the Flaming Cliffs of Mongolia’s South Gobi Desert. At this point I’ve gone full Indiana Jones.

I spit my dinosaur out, returning it to it’s earthen home. Really, it is a bit of a stretch for me to believe that I can determine a species by sticking fragments of bone to my tongue, but since most natural history museums in the US have a strict “no licking allowed” policy when it comes to their fossil exhibitions, it’s hard for me to test this hypothesis. We finish with a walk across the rugged terrain, presumably to reflect on our own significance in time and space, and watch as the setting sun lights the Flaming Cliffs ablaze.

That night back at our Tyrannosaurus-guarded ger camp, my traveling companions and I sit around our felt tents and compare tasting notes and theories about our day’s discoveries. We pass around a bottle of Mongolian Hero, taking turns sipping the stringent alcohol. Of all necessities to squeeze into my one-duffle-bag luggage allowance, I’m glad I packed the vodka. Turns out it’s great for washing the taste of skepticism out of our mouths.

17 Comments